By Judy O'Sullivan

The Rose Bowl Game and Rose Parade entwine like a garland of roses. But sports fans around the globe who yawn their way through Jan. first's floral extravaganza, stay wide awake come game time.

The is the "Granddaddy of All Bowl Games--80-plus-years-old and still kicking. Every major bowl game traces its lineage back to Pasadena. For more than half a century the Rose Bowl Game has been a simple do-or-die play-off between the PAC-10 and the Big Ten.

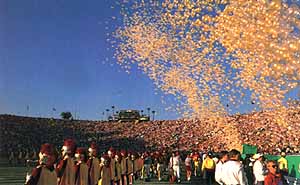

It's very straightforward. College teams representing the West and the Midwest vie for the championship and only grumpy fans truly care who wins by the time the post-party ends--be it celebration or wake. (The conferences are tied 25 games each.) What counts, whether you're in the stadium or an armchair, is enjoying the day, the game, the Goodyear blimp, the Royal Court, the bands, the sunshine and if you're lucky the attar of roses.

The first time the Tournament of Roses tried football in 1902, the event fell short like a badly thrown touchdown pass. Touted as an East vs. West play off, Coach Fielding "Hurry Up Yost" and his boys in blue from the University of Michigan pulverized Stanford 49-0 at Tournament Park on property now belonging to Caltech. Surrendering to the Wolverine captain, the gentlemanly Stanford captain said, "If you are willing, we are ready to quit." (With a bone fracture in his leg, Teddy Roosevelt's second cousin played guard for Stanford.) Fourteen years passed before western teams felt like taking on another cross-country foe.

Only 8,000 turned up to watch William "Lone Star" Dietz lead Washington State to a 14-0 win over Brown. Undaunted, Dietz paced on the sideline clad in top hat, striped pants, swallowtail coat, spats and cane. Brown guard Wallace Wade said, "We were overconfident and took the game as a lark, even attending the parade first." The association lost $11,00 due to the nasty weather.

They shrugged and carried on. The following year, Jan. 1, 1917, dawned sunny and mild. Balmy. Perfect football weather. Over 25,000 eager fans angrily protested a lack of comfortable seating. Oregon defeated Pennsylvania 14-0. The west could hold its own. And more importantly, draw crowds. It was time to build a stadium.

The association put together a financial package by pre-selling subscriptions, 210 box seats for $100 each guaranteed the first ten years. An additional 5,000 seats provided another five. When finished, the bowl was deeded to the city, which then leased it back to the association for the annual game.

Hunt, a popular member of The Valley Hunt Club which he also designed, was busy changing Pasadena's cityscape. The former La Canada Biltmore--now Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy, Polytechnic School, Five Acres Boys' and Girls' Aid Society residences, the Huntington Art Gallery and Library and Occidental College are his. He worked with Elmer Grey of Pasadena Playhouse fame on the latter two. But it was the stadium seen round the world that brought Hunt international acclaim.

Most everyone tells a Rose Bowl story. In 1925, Notre Dame, coached by Knute Rockne, with the legendary "Four Horsemen" defeated Glenn "Pop" Warner's Stanford team 27-10. The fighting Irish attended early mass before the game at St. Andrew's and "prayed for victory"--an unfair advantage according to some Stanford fans, presently senior citizens.

Now home to the UCLA Bruins for almost 16 years, the Rose Bowl hosted the 1932 Olympics and provided a soccer site for the 1984 Olympics.

The Rose Bowl, despite face-lifts, continues to mean down-home college football at its purest to loyal fans and millions of international TV viewers each New Year's Day. Truly, a rose by any other name is the memorable stadium in Pasadena's now park-like Arroyo Seco.